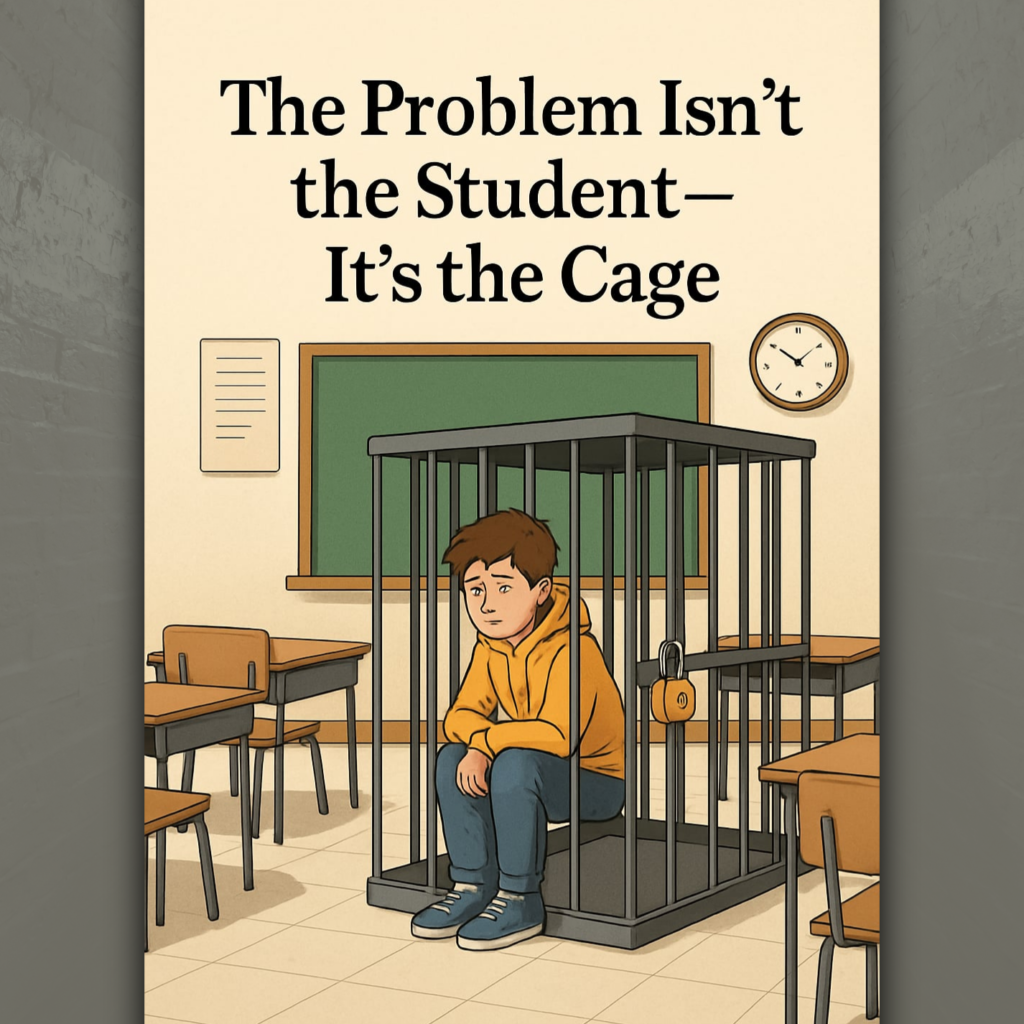

We’re losing too many good kids to a system that doesn’t know them.

Not because they’re broken. Not because they’re lazy, defiant, or disinterested.

But because the very place that’s supposed to help them grow—often feels more like a cage than a community.

A cage of rigid schedules and test prep.

A cage of rules without relationship.

A cage of overworked staff and students who feel like they don’t matter.

We talk a lot about trauma-informed teaching. But what if the trauma isn’t just what kids bring in the door?

What if part of the trauma is what they experience inside the building every day?

Now imagine this: a student, full of potential, entering a school day after day where no one truly sees them—where their voice doesn’t matter, and their strengths are overlooked.

That’s not education. That’s emotional starvation.

And we wonder why they act out, zone out, or shut down.

But before you think this is about being soft or lowering expectations—hold up.

This is about getting real about what works.

Because connection isn’t fluff. It’s the foundation.

And we have science—and real stories—to back it up.

Let me take you to a lab in the 1970s that changed everything.

Enter Rat Park: The Power of Environment

In the 1970s, psychologist Bruce Alexander ran an experiment that shook the foundations of addiction science (Alexander, Coambs, & Hadaway, 1978).

In the original studies, rats were isolated in small, barren cages with access to two water bottles—one with plain water, and one laced with morphine.

Isolated and alone, they drank the morphine-laced water obsessively—often to the point of overdose and death. The conclusion? Morphine was inherently addictive.

But Alexander asked a better question:

What if the problem isn’t the drug—but the cage?

So he built Rat Park—a spacious, enriched environment filled with tunnels, toys, food, and, most importantly, other rats to interact with.

The same rats were moved into this vibrant, social environment and given the same two water options.

And something remarkable happened.

They barely touched the morphine.

Some didn’t drink it at all.

None of them overdosed. Not one.

In isolation, the rats self-destructed.

In connection, they thrived.

Alexander’s conclusion was clear: it wasn’t addiction to the substance—it was addiction to relief from despair. And when despair was replaced with purpose, play, and connection, the need to escape disappeared.

The study didn’t just redefine addiction.

It revealed a truth about all of us:

When life feels empty, we look for an exit.

But when it feels full—we don’t need one.

Our Students Are Caged Too

Make no mistake: many of our students are just as trapped.

Not by steel bars, but by emotional disconnection.

By systems that value standardization over humanity.

By school cultures that punish behavior while ignoring the pain beneath it.

Kids who feel invisible in classrooms.

Kids who walk hallways in emotional isolation.

Kids who show up physically but are checked out mentally and emotionally.

And when they struggle, our go-to solution is the same:

Fix the child.

The Meds Question: What Are We Really Treating?

Let’s have the honest conversation.

Medication has a place. For some kids, it’s essential. Life-changing. Even life-saving.

But what if, for others, medication is being used to mask a deeper issue?

What if we’re medicating symptoms of a broken environment?

A 2019 study published in BMC Psychiatry showed that schools implementing movement breaks, unstructured play, and emotional regulation supports saw dramatic improvements in behavior. Even more, some students were able to reduce or stop their medication entirely—not because their challenges vanished, but because their environment changed (BMC Psychiatry, 2019).

In Texas, a district introduced two recess periods a day along with SEL-based lessons. Teachers reported improved focus and behavior. And under physician supervision, some families reported reducing their children’s ADHD medication.

This isn’t anti-medication.

This is pro-connection, pro-play, and pro-purpose.

Before we label a child, we need to examine the environment they’re in.

Because sometimes, it’s not brain chemistry—it’s emotional starvation.

The Science Behind Connection and Learning

Research backs this up. The Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University emphasizes that “responsive relationships are essential” for healthy brain development. In fact, students who report feeling connected to teachers and peers are significantly more likely to succeed in school.

The CDC’s Adolescent Connectedness Report (2022) found that students who feel connected to school are:

- 54% less likely to experience depression symptoms

- 70% less likely to engage in risky behavior

- More likely to have higher grades and test scores

Bottom line: Relationships fuel achievement.

The Illusion of Connection: Why Technology Isn’t the Answer

We live in the most “connected” time in history, yet students report feeling lonelier than ever. Phones and social media give the appearance of connection, but often serve as a distraction or escape from real relationships. Research from Jean Twenge (2017) shows that teens who spend more time on screens are significantly more likely to experience depression and anxiety. Excessive screen time also correlates with lower academic performance and reduced sleep—both critical to cognitive function and emotional regulation.

Then came the pandemic—and the illusion shattered.

During COVID-19 school closures, students lost more than classroom time. They lost daily interactions, hallway conversations, cafeteria friendships, and even the grounding routines that came with being physically present in a community. It was a social and emotional gut punch.

Even with Zoom classes and digital tools, the disconnect was undeniable. According to CDC Youth Risk Behavior data (2021), during the pandemic:

- More than 40% of high school students felt persistently sad or hopeless

- A third reported poor mental health most of the time

- Suicide attempts among teens rose significantly, especially among girls

Why? Because school isn’t just a place for academics. It’s where many students experience their most consistent relationships, structure, and sense of belonging. The absence of in-person connection revealed just how critical those relationships really are.

Technology couldn’t replace it.

Curriculum couldn’t fix it.

Only connection could.

More Than a Drug Problem: Other Cages Students Face

Addiction may have been the focus of Rat Park, but the broader lesson is about how environment shapes behavior—and today’s cages go beyond drugs.

Chronic loneliness, anxiety, academic pressure, bullying, family instability, poverty, and trauma—these are the new cages. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, 32% of adolescents aged 13–18 suffer from an anxiety disorder. Depression rates in teens have increased by over 60% in the past decade (Pew Research Center, 2019).

And here’s the cost: students struggling with depression are twice as likely to drop out of school (National Dropout Prevention Center). They often experience difficulty concentrating, retaining information, and engaging in classwork.

Social isolation doesn’t just hurt emotionally—it compromises learning.

Neuroscience supports this: when students are stressed or emotionally overwhelmed, the amygdala activates a fight-or-flight response. This bypasses the prefrontal cortex—essential for decision-making, reasoning, and problem-solving (Immordino-Yang & Damasio, 2007). In short, if a child doesn’t feel emotionally safe, they cannot fully engage cognitively.

Connection Reduces Struggle and Builds Resilience

Studies also show that students in relationally rich environments:

- Experience fewer disciplinary issues (Gregory & Ripski, 2008)

- Are more resilient in the face of adversity (Werner & Smith, 1992)

- Have better emotional regulation and executive functioning (Immordino-Yang & Damasio, 2007)

When students feel safe and seen, their brains function better. Connection releases oxytocin and other chemicals that foster trust, memory, and motivation.

And when students know someone believes in them—they begin to believe in themselves.

Curriculum didn’t heal the disconnect.

What the Human Version of “Rat Park” Looks Like in Schools

What does a better environment actually look like?

- Teachers who know every name—and the story behind it

- Classrooms that feel like communities, not compliance factories

- Unstructured play, movement, and curiosity

- Clubs and peer groups that build belonging

- Staff who model authentic relationships

- Discipline that reframes behavior into a path for growth

This isn’t lowering the bar.

It’s raising it by creating an environment where kids can rise.

When students feel safe and seen, they don’t need to escape.

They engage. They learn. They lead.

Final Thought: Stop Fixing the Kid. Fix the Cage.

We’ve spent years trying to fix students who can’t sit still, focus, or behave “correctly.”

But maybe they’re just reacting to a cage that crushes creativity, erases identity, and disconnects them from joy.

Bruce Alexander wasn’t just studying rats. He was studying the human condition.

Change the environment, and you change the outcome.

Shift from control to connection, and students don’t need to cope—they grow.

Relationships aren’t a soft skill—they’re a survival skill.

They aren’t about fluff. They’re about function.

They’re the foundation of healthy development, academic achievement, and emotional resilience.

When we build schools on connection, we’re not just helping kids survive—we’re helping them become their best.

Not trapped in cycles of isolation, disconnection, or despair—but supported, seen, and set free to thrive.

So no—the problem isn’t the student.

It’s the cage.

And the solution isn’t complicated. It’s human.

More connection. More movement. More meaning.

Let’s build schools that don’t confine kids—but free them to become who they’re meant to be.